K-LIT No. 3: Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung

“And in this twisted, wretched life of mine, that single fact remains my sole consolation.”

Read it here: Cursed Bunny

About the Author: Bora Chung

Translated by: Anton Hur

Summary:

“From an author never before published in the United States, Cursed Bunny is unique and imaginative, blending horror, sci-fi, fairytales, and speculative fiction into stories that defy categorization. By turns thought-provoking and stomach-turning, here monsters take the shapes of furry woodland creatures and danger lurks in unexpected corners of everyday apartment buildings. But in this unforgettable collection, translated by the acclaimed Anton Hur, Chung’s absurd, haunting universe could be our own, illuminating the ills of contemporary society.” - DLKL

Thoughts on Cursed Bunny

I thumbed through the pages of Bora Chung’s story collection, Cursed Bunny, before choosing which one to read, and what I saw was the potential to be very scared and very grossed out–feelings I tend to avoid when reading for pleasure. The only one I felt I could read alone, in the silent, dimly lit hours of the morning, was the title story.

Cursed Bunny is told in what I call character-collab (I’m sure there’s an official literary term for it, but I don’t know what it is), something I see a lot in Korean literature. The main POV is the recipient of a story. For a large portion of Cursed Bunny, a grandson is listening to his grandfather tell the family legend of a cursed fetish*** created in defiance of the two forbidden requirements: the creation of cursed fetishes for personal use and the cursing of handmade items. The grandson has heard this story many times, so the narration slips seamlessly between his grandfather’s narration and his own recounting.

Cursed Bunny is a brief, lightly disturbing piece of speculative urban fiction. It’s not a genre I enjoy, but I liked this piece. The story has an unexpected twist at the end that neatly resolves questions I had throughout about the reason for this or that. Anton Hur’s translation is, as I’ve come to expect from him, excellent.

With a translation, I think it’s tricky to look too closely at craft at the sentence level; it’s a useful exercise, but what part is the translator's and what part is the author’s–that’s indistinguishable for a monolinguist like me. I do have access, through the Digital Library of Korean Literature, to the original text, but it’s on hold, so it’ll be some time before I’m able to get a closer look at those sentences.

What I’ll briefly comment on is the structure of the piece, which is delightful. We start with the grandfather telling the story. As it progresses, we are puzzled, we are saddened, we are avenged. And then, after the story, we are surprised. There are hints before the surprise that make it inevitable, and on a second reading, those hints point to the obvious. But initially, the grandfather’s narration is too engaging to be distracted by the grandson’s comments and asides, so we gloss over them. Actually, I thought perhaps Chung had chosen this narrative device of storytelling within the story at the expense of developing her narrator. But I shouldn’t have worried. She’s a BOSS for a reason. The ending layers everything that came before in a coat of fat, deepening the flavor, and making that second helping irresistible.

***Fetish, in this context is not a sex thing, but: an inanimate object worshiped for its supposed magical powers or because it is considered to be inhabited by a spirit. (definition from Google-Oxford Languages). I did not know, until I read this story and looked it up, that this was one of the definitions for the word.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been reading a lot of Park Nohae and Yi Sang lately (and also happily working through Hwang Sok-yong’s Mater 2-10), but I approached this story with two lenses: Postcolonial on the left and Marxist on the right (which I found more useful). These lenses allowed me to pay closer attention to the issues of class struggle in Korea embedded in this piece: the economic injustices in post-war Korea that quietly persist today, the economic burden of children, the criticisms of the Korean government, and the capitalists who achieved wealth through destruction. As the grandson reflects in response to his grandfather’s tearful lament: “But such things are indeed allowed, and such people who allow it are everywhere.”

I think this social critique is an important characteristic of modern Korean literature. Bora Chung discusses the difference between Korean speculative fiction and American and Japanese speculative fiction in this interview:

She says that Koreans have never been the center of the universe, and so the stories are more focused on Korean society. And I think this story is a great example of that. And it makes me want to read more Korean speculative fiction (despite my usual avoidance of the genre), because from them, I can better understand how Koreans see themselves–as individuals and as a society.

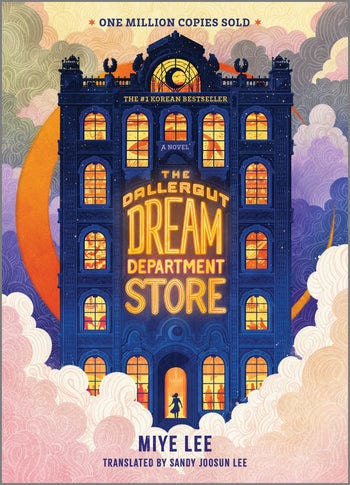

[A small, related sidebar: I read a novel this week called The Dallergut Dream Department Store by Miye Lee, and translated by Sandy Joosun Lee. It’s a light-hearted read and while there are no overt social criticisms in the work, the vignettes of ordinary Koreans that carry the story forward highlight class struggle, how Koreans relate to work, how they relate to each other (shame, honor, filial piety), and a reoccurring theme the works I’ve been reading: what it means to be happy. If their literature is any indication, it seems like something that Koreans are asking themselves. ]

I’ll wrap this up by sharing this interview Bora Chung and Anton Hur did with the Korea Society while promoting their latest translation of Chung’s work: Your Utopia which came out in English in January 2024. When I listen to Bora, I want to read her words, because she asks such compelling questions and she has such profound ideas, and I want to see how these questions and ideas make their way into her stories.

Quoteworthy

“Grandfather used to say, ‘When we make our cursed fetishes, it’s important that they’re pretty.”

“...the bunny was clearly made with love and care.”

“My family would never use a cursed fetish on someone we knew personally, but our neighbors wouldn’t have known that, and even if they had, they wouldn’t have bothered us, anyways.”

“Grandfather’s friend cared only about developing delicious, healthy spirits; he had no idea that in the new, post-war age, connections with government higher-ups, networking, entertaining, and the occasional bribe and backdoor dealing were more important than product quality or technology.”

“And in this twisted, wretched life of mine, that single fact remains my sole consolation.” (The dependent clause of this sentence shook me.)

K-Pop Recommendation:

This recommendation isn’t really K-Pop, but I think you’ll like it, or at least find it interesting. This song, Asurajang*, by the traditional folk singing artist turned modern singer-songwriter, Song Sohee, is another electric piece of social commentary.

1, 2, 3 6, 5, 4 8, 9, 7 100 Even if it’s not what I want to know But you should know this one thing Everything is already falling apart There is no such thing as common sense anymore To uncomfortable words Do you hate being uncomfortable? Inconveniently, this is where I am now It's spinning round and round I didn't expect this either I'm just playing around like a crazy person This world is really crazy Excited in the box I don't want to know Well, you can throw away the essence, that’s okay. In fact, I am here as you know There's only one thing I want looks uncomfortable looking anxious Your pitiful looking face It's spinning round and round I didn't expect this either I'm just playing around like a crazy person This world is really crazy finger speech discussion news It's spinning round and round I didn't expect this either I'm just playing around like a crazy person This world is really crazy Excited in the box

(Translation by Google)

I found the music video appropriately uncomfortable to watch:

*pandemonium; scene of chaos

싸움 등의 이유로 많은 사람들이 몰려들어 혼잡한 곳. 또는 그런 상태.

A busy, crowded place with lots of people due to a fight, etc., or such a state. - Korean Dictionary

K-Lit Recommendation:

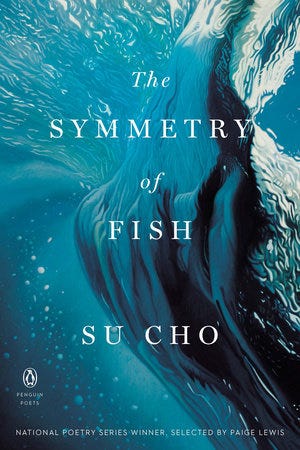

Okay, not K-Lit, but this poetry collection written by Su Cho is gorgeous and cathartic, a must-read for Korean-Americans who will nod and cry and laugh and feel these words deeply. My favorites are: Fermented, Remember This When You’re Hungry, and The Old Man in White Has Given My Mother A Ripe Persimmon Again.

K-Drama Recommendation:

I’ll return to the theme of social commentary with this recommendation: Little Women. A liberal twist on Alcott’s beloved American novel, Little Women shares the story of three sisters, “who only have each other and never enough money, get[tting] entangled in a conspiracy involving the rich and powerful.” A delicious slow burn.

K-Yum Recommendation:

Speaking of delicious, I am obsessed with Ssamjang. I made a huge batch the other day and ate it all in less than 48 hours. I used it as a dip for fresh-cut veggies, and as a paste for lettuce wraps loaded with too-dry shredded chicken. It was wonderful. I am out of doenjang now though, so a trip to H-Mart will have to happen sooner then later.

One Last Thing:

I want to share this substack I found last week that I’m excited about. It’s a substack projected devoted to translating 300 Tang Poems. It’s Classical Chinese translated into English by the Korean writer, Hyun Woo Kim.

He gave a great interview about his work with Claire Chai of Slow Burn Living (another great substack).

The poem below is gorgeous and so beautifully translated. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

Ummm I want to read Cursed Bunny immediately that's my jam. I avoided reading too much of your commentary because I want to read it for myself.