K-Lit No. 4: The Old Hatter

“Oh, the glory of a past whose sun has sunk without even a magnificent final glow!”

Read it here: The Old Hatter

About the author: Yi Mun-yol

Translated by: Brother Anthony

Summary:

“The Old Hatter, the penultimate story of You Can't Go Home Again, Lee's collection of sixteen stories on the theme of the modern Korean's loss of his home town in the physical, spiritual, and psychological senses, reveals Lee's obstinate conservatism but also his genuine and deep regret over the passing not only of a way of life but the frame of mind that created and sustained that way of life. The old hatter is a fine example of a Lee Mun-yeol figure who is pitiful and sublime at the same time.” - Brother Anthony

Thoughts on The Old Hatter:

When I read Korean literature in translation, I’m often struck by how folkloric the narratives are, even in stories that aren’t themselves folk stories. Mater 2-10, Cursed Bunny, and this week’s story, Yi Mun-yol’s The Old Hatter, all use narrative devices that evoke that larger-than-life voice and lend a more traditional sound to modern prose.

The Old Hatter is especially interesting because the story centers on an old man who has devoted himself to a dying trade. Yi Mun-yol’s narrator sees the old man as this legend-like figure. At first, the old hat-maker is an object of derision. But the narrator’s perspective shifts as he grows older and enters a world reflecting the difficulties of living a Western-influenced, capitalist society.

These hats were designed to encase the top knot, a symbol of manhood in Joseon Korea. In 1895, when the Japanese barber chopped off King Gojong’s top knot in front of a crowd of witnesses, the Japanese effectively began the emasculation of Korea, or more horribly, its castration.

In The Old Hatter, there exists a tension between modernity and tradition, and in my life, there exists a tension between me and my mom.

Differences between generations within one culture can be difficult, but reconciling differences between generations across two cultures seems impossible. Sure, we can do a mash-up of 70’s rock and 2010’s rap (my Orangetheory studio plays generational remixes all the time), but have you ever heard, or wanted to hear something like this:

mashed up with something like:

I’m sure remixes across both generations and cultures exist, but my point is that it’s tricky. And likewise, so is communication between my mom and me. It’s taken a long time to understand why.

When she thinks that my response to her offers of unsolicited (sometimes hurtful) advice should be my profuse gratitude, it comes from a culture that taught its children such lessons like Yi’s narrator laments have been lost:

I mean, my mom’s not that old, but her parents would have heard these stories as children, and so I know these stories still live somewhere in my mom’s imagination. These “old lessons” were at one time, part of the fabric of familial beliefs in Korea.

My mom was born and raised in abject poverty; she didn’t finish elementary school. Instead, she worked in a factory sewing letters on hockey sweaters. She didn’t Westernize, or modernize, through a formal education system like much of Korea did during her youth. As an adult, she moved to America, became a Christian, earned her GED (in English, which is amazing, because she only went through 5th grade in Korea), and remains staunchly conservative, a culturally traditional Korean in many ways. She has been in America for most of her life now, in it but not (culturally) of it. As a result, even the language my mother and I share is devoid of that culturally contextualized understanding.

The old hat-maker’s daughter is a minor character, but I relate to her. She’s modern; she decides who she wants to marry and runs off, and when her father dies, she comes back to town just long enough to sell the hat store. Yi Mun-yol seems to want us to feel this as a tragic ending. At first, I didn’t think it was. His daughter seemed practical. In fact, I felt like the old man was selfish because he couldn’t let the past go and move on, not even for the sake of his daughter.

But then, I thought about it.

See, I can understand why the daughter was ready to move forward, to be away from the archaic and unfamiliar. But where was her compassion? Where was her sympathy? Her father was experiencing a tremendous loss of identity, the extinction of not only his craft, but his worldview. That’s catastrophic.

When I think about my mom, and her insistence on communicating in a way that recalls archaic and unfamiliar beliefs, my instinct is to force (American) modernity on her. This is how we do it here. This is how we do it now.

But I love my mom. Of course I do. And I want to be able to talk to her. And so maybe I need to recognize the Old Hatter in my mother, and respond with the compassion his daughter, in the whirl of her own life’s progression, couldn’t take the time to give.

When I read this story the first time, I thought it was…fine. At least it wasn’t scary or sad, or overly depressing. I’ve had a little too much of that lately. But I wasn’t excited about it.

After the second read (and I highly recommend second reads, especially if you don’t like something), I realized that Yi Mun-yol is doing much more here than just criticizing society for modernizing. It’s the way we’ve chosen to modernize, I think—without reverence for those who came before us. We eschew the traditional because it’s tradition; we embrace the modern because it’s progress. We don’t recognize the price of each step forward. (Sidebar: I read something recently that said Korea was trading its culture via K-pop for soft power. I think Yi Mun-yol would agree.)

I’m not saying the next time my mom tells me all the ways I’m doing whatever it is I’m doing wrong, I’ll just smile and nod and say, 고마워요 어머니.

No—first of all, I always feel a little weird speaking the little Korean I know to my mother (and other Koreans). No, because I’m American, and we just don’t smile and nod when we’re told we’re wrong. (Should we? Maybe. Probably.) BUT. Next time, instead of getting defensive, I might remember where my mom comes from, the context of her words, and simply say, “Thanks, mom.”

If I didn’t like The Old Hatter at first, I can appreciate it now. Like any good story, it made me think about my life, and it challenged the way I thought about things. Brother Anthony, whose translation of this story is linked above, writes that Yi Mun-yol:

“is a ‘must’ reading for those who want to understand the Korean culture and the burdens contemporary Koreans carry.”

I think I see what he’s saying. I look forward to reading more of Yi Mun-yol’s work soon.

Here are two interviews I think provide some beautiful insight into the Yi Mun-yol and his craft.

Korean Literature Now - given by Yi Mun-yol

The New Yorker - given by Heinz Insu Fenkl, the translator of Yi’s story, An Anonymous Island.

Quoteworthy:

“Oh, the glory of a past whose sun has sunk without even a magnificent final glow!”

“And there was something comic about an old man who clung to his old trade despite constant losses.”

“We did not blame the old man. Rather, we felt profound pity for what resembled the last defiant fury of a cornered beast.”

K-Pop Recommendation:

100% obsessed with this collaboration between AKMU and Lee Sun Hee (talk about a fusion between old and new!):

The music video is troubling, but worth the watch.

K-Lit Recommendation:

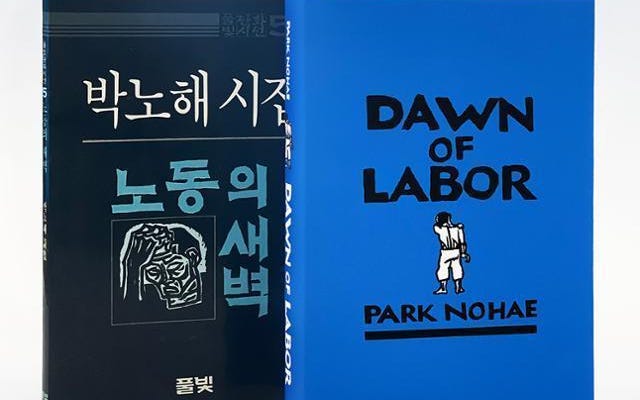

I’m reading, over and over, this collection of poems by Park Nohae.

I listened to this interview with the translator about the work. I hadn’t heard of Park Nohae until I listened to this interview, so it was such a rabbit hole discovery for me.

If you want to read one of his poems, here’s an especially moving one translated by Hae Yeon Choo and Eunsong Kim for the Poetry Society of America:

A Burial for Hands On this Children’s Day He had wanted to go to an amusement park Holding the hands of his wife and son, Jeong who used to smile sucking on a cigarette, His hand now severed off And because he was in his work uniform Neither the CEO’s luxury vehicle, Nor the factory owner’s sedan, Or the manager’s car would take him So after bleeding out for some time and then Holding the back of a truck he went to the hospital His caught hand was still squirming in the machine when I took it out from its greased covered gloves And I cannot speak looking at his 36 long worker years hand Holding his hand now wrapped in a plastic bag to my chest I searched for Jeong’s hilltop home in the mountain district But upon seeing his wife’s gentle eyes and Their bright son I do not take it out to give them nothing but his hand Slumped down at the corner shop in the mountain district during broad daylight Emptying a soju bottle And because Jeong had asked for books on worker compensation, I leave To rummage the downtown bookstore they said was the biggest But goddamn scouring through the mountainous pile of books and Not a single one for a worker On this sunny spring day in the downtown streets of Seoul Fashionable men and women pour in and out Pierced with spring light and Like a mall scene out of some American film All their glittering goods stamped with shiny foreign branding And me in my worker shoes I shrink down like an escaped prisoner The cars are lined up in front of the luxury high-rise spa Packed in front of the fancy upscale bar And the gigantic department stores are simply overflowing There’s loud chanting at the pro baseball stadium All while like knives in the night workers are working our asses off During this time Why are there so many assholes relaxed, having fun These people can get whatever they want They can have whatever they please So in the middle of this downtown street in this advanced nation I become ET And wander endlessly like a raving lunatic To return to the factory as a worker paid $4.8 a day Stamping my card for overtime On my chest Jeong’s cold hand Cools down and becomes swollen blue blue swollen so We wash his hand with soju And bury it in a sunny spot underneath the factory wall The exploitative hands who On the blood sweat backs of workers Devour the prosperity of this nation We bury Their do-nothing but be jolly and merry white hands We chop chop them cleanly with the press machine And bury them bitterly with tears Until our working hands Can thrive delightfully until then We bury their hands again and again

One Last Thing:

Next month, I’ll be rolling out the K-Lit Writes craft exercises! These will be bi-monthly writing prompts inspired by Korean authors and poets. I hope you’ll join me for that. :)

What an interesting article! I haven't thought before that the narratives of Korean literature are folkloric, but I think you have a point.

Regarding Yi Mun-yol, I think he is a deeply troubled man inside. His father defected to North Korea due to ideological reasons, leaving his family to be persecuted in the South. Yi has become a staunch anti-communist ever since, and becoming an outspoken anti-communist in South Korea often meant being pro-Japan, pro-American and pro-authoritarian regime. Thus, his understanding of "tradition", from the way I see it, seems to be somewhat detached from the historic-political realities and many times embodied only through depictions or implications of Korea's idealized past. It is likely that he understand this himself too. There are other works where his attitude towards pre-modern traditions oscilate between scoffs and laments. Although, maybe it's not just Yi who is deeply troubled inside, but it's the whole South Korean society which went through modernization/westernization/colonization.

I have not read Yi Mun-yol, but I am now interested - especially how you described: "It’s the way we’ve chosen to modernize, I think—without reverence for those who came before us. We eschew the traditional because it’s tradition; we embrace the modern because it’s progress."

In my time living in Korea from 2003 - 2014, I saw some of that hyper modernization from an expat's point-of-view. Even from my small window into Korean society, largely focused on Seoul, I could sense things changing.

I think you put it well having read that "Korea was trading its culture via K-pop for soft power." For me, I have been watching and re-watching Korean movies such as "봄 여름 가을 겨울 그리고 봄," "친구," "파묘." There is a certain spirit to these movies that I cannot quite identify, but it transcends the typical popular type of movies and K-dramas. I would put "파묘" with those Korean movies of the early to late 2000s in Korean cinema. There is something timeless about movies like that.

Thanks for sharing. I am looking forward to the craft exercises next month!